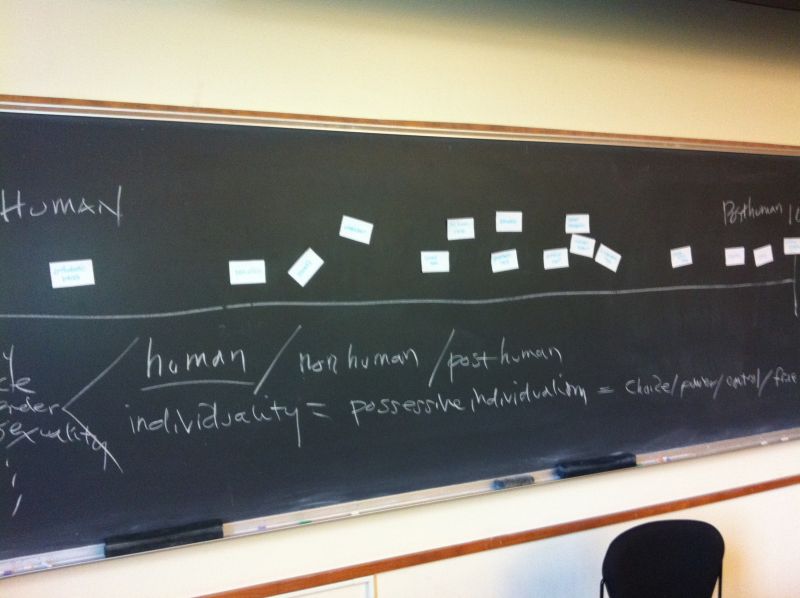

In my CHID 250 C: “Mediating Identities” class this past week, I did a “new” exercise where I put on the board a continuum line with “human” and one end and “posthuman” on the other. The class this week is on “posthumanism and identity,” and we read the introductions to N. Katherine Hayles’s How We Became Posthuman, Cary Wolfe’s What is Posthumanism, Thomas Foster’s The Souls of Cyberfolk, as well as the “Transhumanist Declaration” and selections from the “Transhumanist FAQ.” While sussing out the differences (and alliances) between terms like human, transhuman, posthuman, and nonhuman, the exercise above asked students to think about how naturalized (or no) certain technologies have become, how imbricated (or inextricable) they have become with definitions of the human (or not).

Students were randomly given a card with a range of technologies, including: fire, eyeglasses, automobile, prosthetic limb, glass eye, bacteria, sheepdog, penicillin, make up, tattoo, military drone, artificial intelligence, cyborg, artificial heart, combat exoskeleton, cybernetic eye, nanites, and so on. Then, as a class, they decided where their particular technology, where their card fell on the above line. It was interesting to see where they placed certain things and what their rationale for that placement was, particularly when one technology butted up uncomfortably against another. For example, we talked about the continuum as temporal, even teleological and whether they wanted to resist putting “older” technologies more toward the “human” and “newer” ones toward the other end. We also talked about the desire to rank the degree of modification, transformation, or instrumentalization and how they also affected the “intensity” of the (post)human. So, “eyeglasses” were tools, corrective, separate from the body and therefore naturalized as more human but a “cybernetic eye” was invasive, artifical, and futuristic and therefore more posthuman.

Most important and interesting were the things that got placed outside of the continuum (a critical leap they made on their own). Things like bacteria and fire did not seem to fit neatly into the implied scale and could occupy both ends simultaneously. Therefore, the students pulled them out and puzzled over what to do with technologies that were either wholly “natural” or at a scale (historical, geographical, cosmological) that defied simple placement.

It was a good teaching day (and hopefully learning day, too).