In December 2010, almost three years ago, I wrote a piece for the Critical Gaming Project at the University of Washington on Zynga’s Frontierville and queerness. I want to reblog/reprint/redux that post in part to preserve it here and in part to return to some of the ideas. At the end of the 2010 post, I linked to an Extra Credits online video about diversity in games. In 2012, the web “show” has released a subsequent video specifically on “sexual diversity:”

The challenge with the above video (and the issues about diversity be they about race, gender, sexuality, et al.) is that they boil much of the conversation down to arguments about individuality, character “depth” and development, and more abstractly that games are “better” when they appropriately (who gets to decide this is precisely unremarked upon) include “diverse” content. Diversity then becomes flattened — as it so often happens — into tokens, shadows, subtext, political correctness, and an antidote to normative guilt. As I have argued elsewhere, the challenge for “queer” games is not simply to include more “diverse” characters, plots, or choices. Rather, these design choices all too often get conflated with the interactive fallacy of player and character choice and power in video games. Instead, as I have argued “queer games” need to challenge all strata and dimensions of game creation, development, design, programming, marketing, consumption, and of course, play. But more on this later. For now, a blast from the past…

“Frontierville, A Casual Queer Reading”

Reblogged from: https://depts.washington.edu/critgame/wordpress/2010/12/frontierville-a-casual-queer-reading/

As I was re-reading the introduction to Jesper Juul’s A Casual Revolution: Reinventing Video Games and Their Players and thinking about what I could possibly say about the current bumper crop (pun intended) of web-based, social networking-based games (like the Zynga oeuvre, including Farmville, Mafia Wars, Cafe World, and now Frontierville and Cityville), I am struck by the following passage:

Mimetic games move the action to player space, but many of them also encourage short game sessions played in social contexts. Such games, like all multiplayer games, are socially embeddable: games for which much of the interesting experience is not explicitly in the game, but is something that players add to the game. For example, if playing a competitive match of Guitar Hero or Wii Tennis, the game takes on meaning from the existing relations between the players. Playing a game against a friend, a significant other, a boss, or a child, adds meaning and special stakes to the game. Furthermore, people playing mimetic interface games are often themselves a spectacle, making these games more interesting even for those who are not playing. (Juul 20)

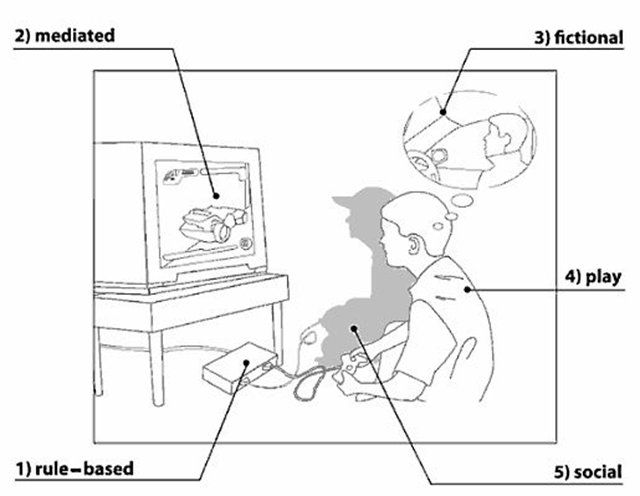

What is remarkable here is not Juul’s anecdotal account of why people play casual games or how people play games casually. Rather, I want to focus on his theorizing about these games being socially embeddable–a term that I think goes beyond any vernacular notion of “social network,” and a term that seems to hint at more than the (almost banal) account of games requiring and articulating a social or cultural context. For example, see the following illustration from Michael Nitsche’s Video Game Space (cf. Ian Bogost, Edward Castronova, Jesper Juul):

What is remarkable here is not Juul’s anecdotal account of why people play casual games or how people play games casually. Rather, I want to focus on his theorizing about these games being socially embeddable–a term that I think goes beyond any vernacular notion of “social network,” and a term that seems to hint at more than the (almost banal) account of games requiring and articulating a social or cultural context. For example, see the following illustration from Michael Nitsche’s Video Game Space (cf. Ian Bogost, Edward Castronova, Jesper Juul):

What is important here is not that video game studies is suddenly realizing that games are being played by people, that games are being shared between people, and that games are played across communities, social locations, cultures, even politics. What is important here is to take Juul’s definition of social embeddedness and extend it, adding it to something like Alexander Galloway’s claim that “video games render social realities in playable form” (Gaming 17) or Constance Steinkhueler’s argument that games “are a ‘mangle’ of production and consumption—of human intentions (with designers and players in conversation with one another), material constraints and affordances, evolving sociocultural practices, and brute chance” (“Mangle of Play” 200). In other words, the social embeddedness is about more than just an “interesting experience” but more importantly about what “players add to the game” in terms of social, cultural, and economic “constraints and affordances.” What the players bring to the game, what the players get out of the game, and what the game mediates requires close attention and careful close playing.

So, I turn to a simple but telling example: Zynga’s (newish) game Frontierville, which is described by the game company’s site where players can: “Build a sweet li’l homestead, a big ol’ family and a boomin’ frontier town!” and “Explore a new life on the frontier. In the untamed wilderness, frontier settlers join fellow pioneers to chop trees, raise livestock, and plant crops.” The Zynga formula, for which the game company has been both praised and reviled, holds true for Frontierville. The game promises a symphony of pointing-and-clicking. Like other Zynga games, “playing” the game amounts to dollhouse management, a kind of spreadsheet-skinned-as-video game sort of play, clicking on in-game items (e.g. plots of land, decorative features, animals, building). Each click then represents an action: plowing, planting, harvesting, petting, moving, deleting, and so on. The game capitalizes on the very kind of usability and user-interface literacy that has become naturalized by the web and by applications like Microsoft Office. It makes sense then why games like Frontierville are so “user friendly” and popular among casual gamers, particularly those who spend a lot of facetime with a computer screen.

What’s new about Frontierville, though, is Zynga’s attempt to make the game more game-like. Unlike its predecessor Farmville, Frontierville is better looking, offers a wider variety of point-and-click tasks, and pushes a more robust quest system requiring collaboration from “neighbors” (friends who are also playing the game). In fact, it is said that Zynga wanted Frontierville to be even more social, almost to the point where if a player does not have a sufficient number of neighbors, the game is nearly unplayable given the vast number of clicks-to-gift and clicks-to-return needed by the game’s quest economy. The irony here, of course, is that in order to make the game more like a game, Frontierville must in a sense sacrifice its casualness–the very thing that draws players to the game in the first place.

But game mechanics aside, Frontierville also reveals a more troubling “mangle.” Beginning with its name to the cartoony caricature of “frontier” life and inhabitants, the game on the one hand evokes a particular historical and geographical moment (American colonial history, manifest destiny, settling of the North American West) and the romanticized, nostalgic images and narratives of prairies, settlers, cowboys, log cabins, and simpler times. Beginning the game is “rough and tough” because you have few resources and you must “clear” the lad and safeguard it against “varmints” (like rattlesnakes, foxes, gophers, and bears). However, as the game waxes, if you can persevere and tame the wild west, you too can raise a family and found a “boomin'” town. Granted the game is ripe for sociocultural analysis given its rather whitewashed history and politics. I have to ask: Where are the Native Americans in all of this?

The mangle of Frontierville is not all “bad” though, and I offer a singular moment of interest, of possibility. Though contingent and not deeply thought through (by game or by its players, I would imagine), the game does allow for a queer reading. I must stress that the game is still framed and predicated on heteronormativity–your success is in part largely determined by whether or not you start a family. However, the game’s “family missions” do allow for some flexibility in imagining what that family looks like.

Right from the get go, one of the first mission of the game is to make sure your homestead is prepared and ready for the arrival of your “spouse-to-be.” Here the game makes allowances for the player to imagine who that spouse will be. By refusing to assume the gender of the forthcoming spouse, the game opens a space for queer possibility. Granted, unless the player refuses to pursue the family quest lines, the game still assumes that you want, need, and have to have a (ostensibly monogamous) spouse. Once you begin the marriage line, you must complete several quests in order to prepare for the arrival of your spouse, including gathering money, resources, fancy clothes (for the wedding), and building a house. As soon as you can prove that you are a worthy suitor and a capable provider, your spouse arrives and the player is given the opportunity to design the avatar.

Like the the initial character customization screen for the player’s primary avatar, the spouse-to-be can be similarly manipulated and decked out. The player can change hair, features, skin color, dress, and gender. Here then the player can elect to have a different-sex partner or a same-sex one. (Note the realities of gender here are only imagined as male and female, man and woman, and encoded along gendered lines, masculine and feminine right down to the blue and pink icons.)

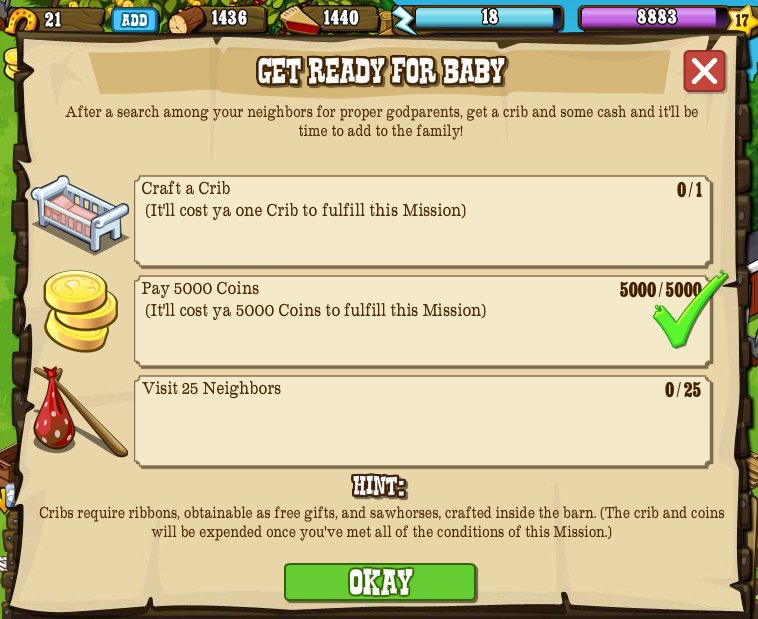

By allowing the player to choose a same-sex spouse, Frontierville joins the ranks of very few games that even imagine much less allow for queer play. And as I said earlier, most of this queering is only window dressing; there are no direct in-game advantages or consequences for choosing one spouse over another. The addition of the spouse avatar, in terms of game play, allows for the player to switch back and forth between the two characters to queue point-and-click tasks on screen. Both avatars can be employed to work the homestead. Later, the game continues the family missions to prepare for and have a child (again, it’s assumed that a child must be the next logical step in constituting a family, that the nuclear family as imagined by the twentieth century is mapped back onto an “earlier” time). The mechanics for choosing the “kid” is the same as above.

Hedges and caveats aside, what I like about this queer possibility in Frontierville is that a nontraditional family can be created and played. Though the composition of the family has little bearing on the game itself, the fact that this is “something that players add to the game” (Juul 20), which renders a very different kind of social and cultural landscape, is key. It doesn’t make Frontierville a progressive game but it does make it more interesting. It provides ways for the players to think about and perhaps challenge the narratives and norms assumed by the game. Let’s just leave it at that for now. The rest of the long list of issues and concerns and interventions are for another day.

Hedges and caveats aside, what I like about this queer possibility in Frontierville is that a nontraditional family can be created and played. Though the composition of the family has little bearing on the game itself, the fact that this is “something that players add to the game” (Juul 20), which renders a very different kind of social and cultural landscape, is key. It doesn’t make Frontierville a progressive game but it does make it more interesting. It provides ways for the players to think about and perhaps challenge the narratives and norms assumed by the game. Let’s just leave it at that for now. The rest of the long list of issues and concerns and interventions are for another day.

I leave you with The Escapists‘ “Extra Credits” vlog on “Diversity” (which is a good start but…):