Over the past few years (and academic markets), I have been struck by the desire for and necessary requirement of certain game studies jobs for “makers,” people who create, design, code, prototype, and play games. Most of these jobs are for coder-makers, specifically, but the field has made room for other kinds of game makers and gamers. Sadly, even though I have written and designed two games–Tellings, a table-top pen-and-paper role-playing game, and Archaea, a live-action role-playing and wargaming system–I am largely illegible (and ineligible) for these maker positions.

I vowed this past spring that I would spend the summer trying my hand at making, specifically making some sort of digital game (no matter how small). Alas, life had different plans for me (as per usual), and I ended up getting a new job, having to move across country, and setting up shop in a new house, a new town, a new school, a new department, and a new position. All of that change has been very good for me and my career but very bad for making time to make.

But the spark was still there and in the past month or so I have been on my version of a making tear. (It actually reminds me of the playful mania I get into when I make props and equipment or sew costumes for playing and teaching Archaea.)

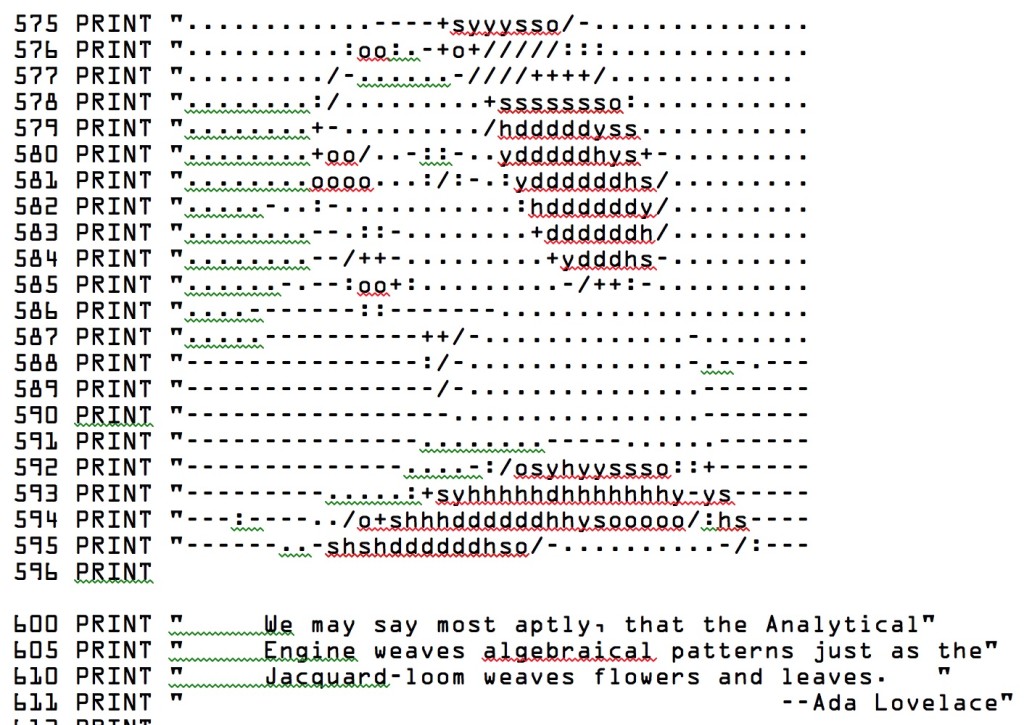

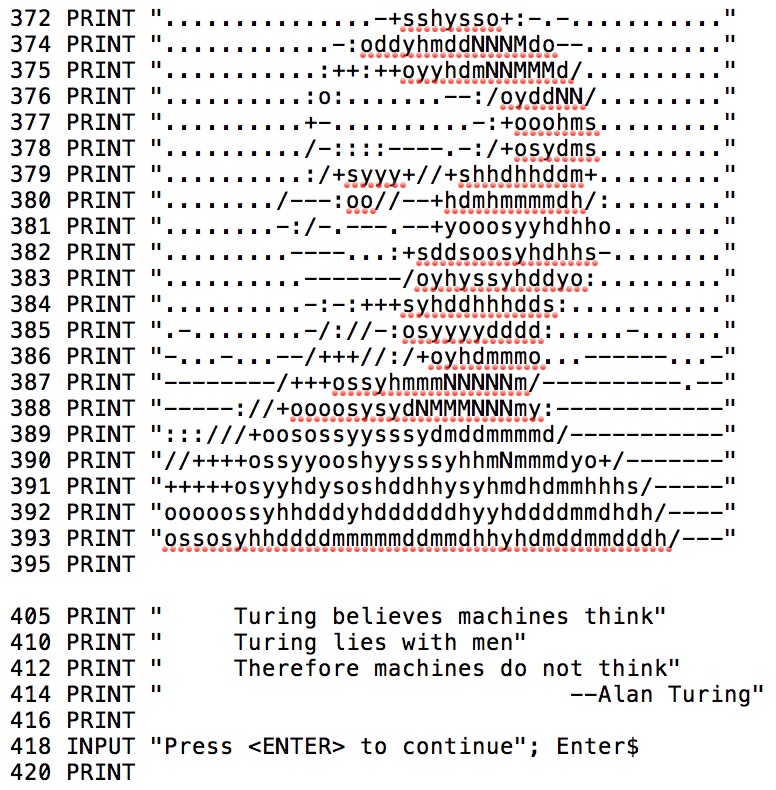

At the end of October/beginning of November, I (finally) finished and turned in an essay for my friend and colleague Adeline Koh’s edited collection on Alternative Histories of the Digital Humanities (forthcoming from Punctum), which I wrote in the form of a BASIC program. The essay is meant to be readable as a traditional essay as well as executable code. The program is a very simple text adventure that lets a reader play through the essay and experience (hopefully) some of the concepts about the technonormativity of code I am thinking about and working through. The essay will be published as code, and I hope to be able to host the essay as an online executable. I have not gotten my revisions back yet but am confident it will make it to print and to play.

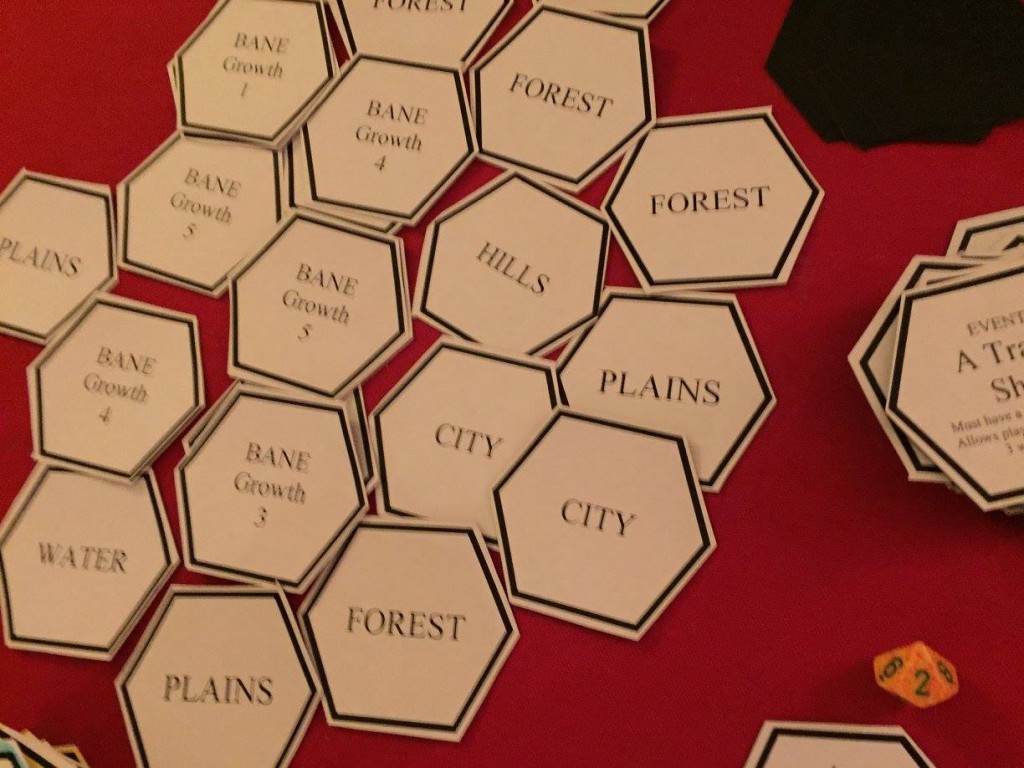

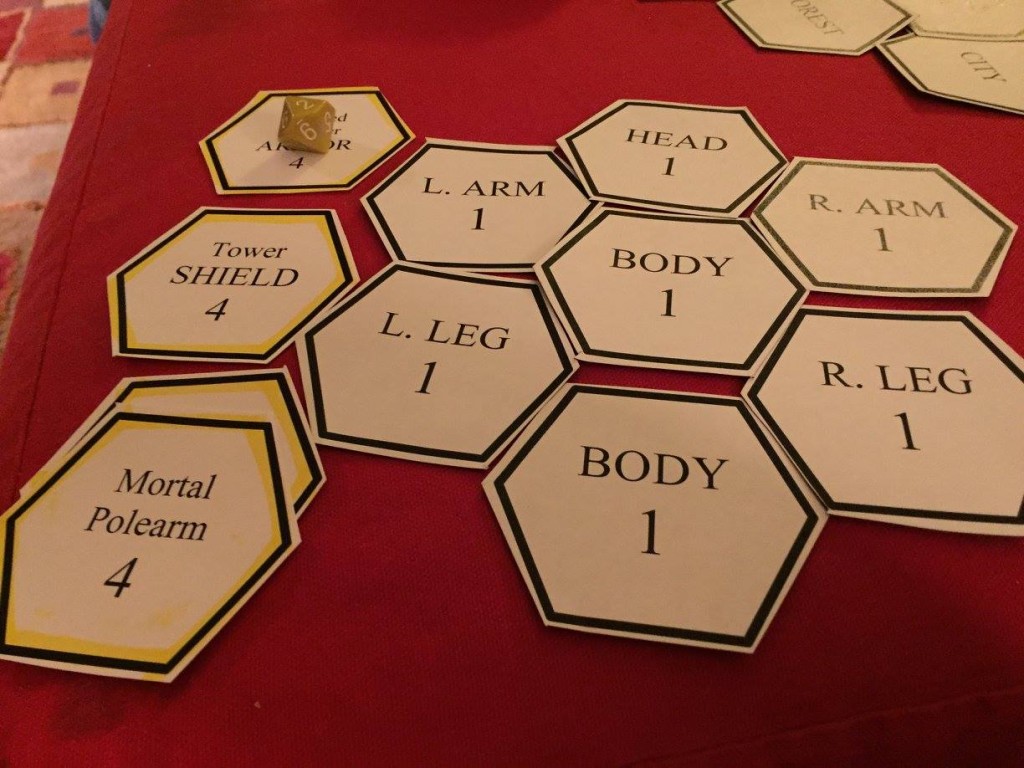

Once I submitted the essay/game, I turned my mania toward a different kind of game. Archaea: Bane, a card game based on the Archaea live-action role-playing game world. I started sketching ideas for the card game in September but did not really sit down to work through the ideas till after the summer. I wanted to create a cooperative, semi-autopoietic card game. In other words, most card games I have encountered are largely competitive, meaning players versus players. I wanted my game to foreground cooperative play (though it, of course, could be played combatively). Since the game is about players helping players, there had to be some sort of challenge, adversary, or goal.

Here is where I borrowed the Bane from Archaea. According to the Archaea rulebook, the Bane is a malevolent power, force, entity that resides in the realm’s underworld:

Many millennia ago, far into the misty past of the Lost Age, it is said that the Icuni flourished in enlightenment and harmony. However, as the fragmented records of the Age reveal to mistic scholars, such prosperity and illumination came at a cost. It is said that with great effort, with powerful rituals, and with the aid of an ancient relic called the Staff of Channeling, the Icuni divorced themselves of every shred of evil, vice, fear, and hatred. Unfortunately, the blackness and the darkness could not be destroyed. Therefore, the Icuni contained it, imprisoned it, collapsed it upon a small island in the middle of the inner Archaea Sea. Then, with cataclysmic magics, the Icuni sank the island in the hopes of forever sealing the evil below…In 1353 CE, on di mita noc–the Day of the Night Path or the winter solstice, evil erupted into the Realm. On that fateful day, the first manifestation of the Bane destroyed a small village near Caven, Josson. The ground simply turned dark as if stained by pitch, the sky grew cloudy blocking the sun, and the air grew cold and perfectly still. In an instant, like a wide sinkhole, the earth simply swallowed the village and all of its inhabitants into an inky pit. Everything disappeared and the ground returned to normal as if nothing had happened. Across the Realm, all sensitive to the ebbs and flows of the Mists felt the rising evil and the loss of life. Auguries into the event revealed only a single but vast presence–the Bane.

The Bane would be the card game’s adversarial mechanic; the Bane would play against the players hoping to thwart them, confound them, overcome them. The basic set-up of Archaea: Bane is that there are two decks: the Player Deck and the Bane Deck. Players draw from the Player Deck (white cards) and the Bane “draws” from the Bane Deck (black deck). Here is where the semi-autopoietic mechanic comes in. Basically, each round of the game starts with a card being pulled from the Bane Deck, which then directs the behavior of the manifestation of the Bane–be it an attack, a world event, a monster, or a spell. The players then must resist and defeat the Bane’s powers and minions and ultimately to destroy the manifestation itself, removing all of the Bane’s cards from the field of play.

On a long train ride from Eugene to Seattle, I made a quick prototype of the game in Microsoft Word. I decided on hexagonal cards, which mimic the hex maps of table-top games, with simple text and values. I wanted to see if the game’s central mechanics made sense and what would need to be adjusted, revised, rewritten, or abandoned. The first play-throughs (with only two players) worked out really well. The Bane is definitely formidable. And the Player cards will need a little bit of beefing up. I hope to have a second draft of the game soon, and I hope to play with a group of four players to see how the mechanics hold up. It has been a wonderful and worthwhile experience. Maybe the enjoyment is because I am already invested in the world of Archaea. I think the game is fun, though, and I think others will, too.

Who says I am not a maker now?